De besturing van een fiets

Van het rijden van een fiets, kan menig kind van vijf zo een demonstratie geven. Met de besturing van een fiets, bedoel ik het ontwerp en de gevolgen van de keuzes van wieldiameter, vorksprong (doorbuiging) en framegeometrie. Welk krachtenspel ontstaat er, en welke theorie voorspelt de stuureigenschappen. Door de geringe massa van de fiets t.o.v. de rijder, heeft deze een sterke invloed op het stuurgedrag. Dit is een complicerende factor, die moeilijk in formules is te stoppen. Rond 1886 krijgt de besturing van de Rover Safety uit Fig.1a de vorm die men in bijna alle ontwerpen toepast.

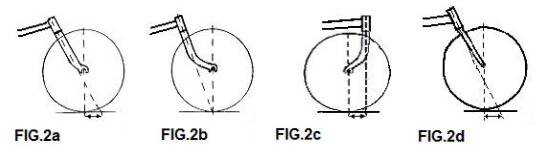

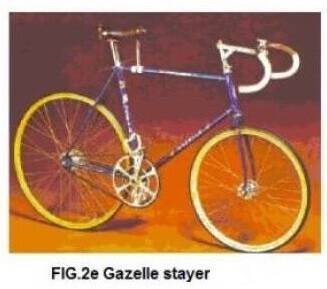

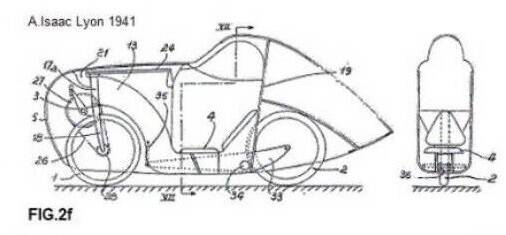

Als de naloop nul is (FIG.2b), heeft de fiets geen eigen stabiliteit meer. Bij nog sterkere doorbuiging krijgen we “voorloop” en wil de fiets alle kanten op behalve rechtdoor; dit is vermoeiend en gevaarlijk! Sommige voorvorken zijn niet gebogen maar recht. N.B. Deze vorkschedes maken wel degelijk een hoek met de binnenbalhoofdbuis, zodat de naloop niet te groot wordt! (Zie FIG. 2d). We kunnen in principe ook een naloop krijgen door de vork om te draaien, zoals bij FIG.2c; dit wordt o.a. toegepast bij stayerfietsen (FIG.2e) en voorwiel aangedreven ligfietsen als Bokhorst en Minq. Maar ook die hadden al een gestroomlijnde voorganger, zoals blijkt uit deze patentaanvrage van Augustin Isaac uit Lyon in 1941.

FIG.1a De geometrie van het voorframe. Er zijn veel experimenten bekend met balhoofdhoeken (B), wieldiameters (D) en vorksprong (V). We kunnen een vorksprong krijgen door vork te buigen, door rechte vorkpoten een hoek te laten maken met de balhoofdbuis, of we zetten de vorkpoten gewoon een aantal centimeters voor het balhoofd. De naloop N en de effectieve naloop M ( = mechanical trail , de belangrijke waarde), liggen vast als we de eerste drie gekozen hebben. Met B, D en V kunnen we na wat wiskundig goochelwerk berekenen dat:

M = (0,5 . D . cos B - V ) en N = (0,5 . D . cos B - V ) : sin B.

Het optillen van het frame tijdens het verdraaien van het stuur, zie FIG.1b , is een belangrijk effect van de vorksprong V. Als we het stuur 90 graden draaien, wordt het frame over de hoogte H opgetild. Als we minder draaien, wordt het frame ook minder opgetild. Rechtdoor gaat via het laagste punt en dat kost het minste kracht. Als er meer gewicht op het voorwiel drukt, zoals bij een tandem, zal er meer gewicht opgetild moeten worden en merk je dit effect beter.

Om te zien wat het effect was, bouwde de onderzoeker David Jones fietsen met voorvorkgeometrieën, die tegen alle bestaande wijsheid in gingen. Hij probeerde een onberijdbare fiets te bouwen. Al zijn creaties bleken na wat oefening toch berijdbaar; de mens kan zich blijkbaar goed aanpassen: de redding voor menige ontwerper! David Jones introduceerde een stabiliteitsindex U. Fietsen hebben goede stuureigenschappen als deze tussen -1 en -3 ligt ; bij de hogere waardes, als -1, wordt de fiets instabieler; bij lagere waardes, zoals -3, is het zelfcorrigerend effect groter. Je moet het stuur dus iets verder draaien voor je de bocht om gaat, en het stuur trekt zichzelf sneller recht. In het blad FIETS gaf men deze u-waarde vaak weer bij de framegegevens. Hoewel de u-waarde dus gebruikt wordt om de stabiliteit van fietsen met eenzelfde wieldiameter onderling te vergelijken, (zoals bij een test van verschillende racefietsen), blijkt het theoretisch model van Jones niet goed genoeg om een absoluut oordeel te geven.

Als we het evenwicht bewaren op de fiets, zijn we voortdurend bezig met kleine correcties; we slingeren lichtjes om ons eigen spoor. Ons evenwicht wordt bepaald door de plaats van het zwaartepunt (eng. COM = center of mass) ten opzichte van het vlak door het hoofdframe. Zodra we een bocht naar links willen maken, sturen we eerst (onbewust) even naar rechts, om het zwaartepunt links van het framevlak te krijgen. Door de zwaartekracht worden we nu naar links en naar beneden getrokken; er ontstaat door de rijsnelheid echter een centrifugaal (="middelpuntvliedende") kracht die ons naar buiten en weer omhoog drukt. Het effect is dat we gaan overhellen in de bocht. Hiervoor is een reactiekracht (=grip) nodig van de banden; bij ijzel vallen we al gauw.

Bij hele lage snelheden ontbreekt de centrifugaal-kracht en balanceren we met ons zwaartepunt boven de raakpunten van de wielen. Voor elk frame geldt, dat de fiets pas stabiel rijdt boven een bepaalde snelheid. De ouderwetse omafiets is sneller stabiel dan een criteriumracer. Gewoonlijk liggen deze waardes rond de 20 km/u (6 m/s). Bij deze snelheid zal de fiets ook zonder berijder stabiel zijn en kleine verstoringen zelf corrigeren! Er is bij experimenten met een rijderloze fiets, gebruik gemaakt van kleine vuurpijltjes die op het stuur gemonteerd werden. Als de fiets zichzelf niet stabiliseerde, en na ontsteking het stuur naar links draaide, dan viel de fiets naar rechts om! Dit bewijst dat we naar links sturen om naar rechts te gaan. Als de snelheid van de rijderloze fiets te laag of te hoog wordt, zal de fiets langzaam in een trage bocht naar links of rechts omvallen.

De armen van de rijder dienen als demper van trillingen. Dit is een belangrijke functie: zonder demping kunnen trillingen uitgroeien tot een shimmy; dit is een steeds sterker worden trilling om de lengteas van het voertuig. Shimmy's hebben te maken met de eigenfrequentie van het voertuig en treden bij een, voor die fiets, specifieke snelheid op. Een oorzaak van het ontstaan van trillingen is de trap-frequentie. De plek waar we kracht zetten, het pedaal, ligt buiten het vak door het frame. Zeker als we stevig trappen, zal er een verschuiving zijn van het evenwicht, en daarmee kan een lichte slingering in het stuur ontstaan. Omdat er twee pulsen per trap-omwenteling zijn, liggen de frequenties gewoonlijk tussen de 1,5 en 4 Hertz. De eigenwaardes van het frame zouden boven de 5 Hertz moeten liggen.

Ook regelmatige trillingen van het wegdek (kasseien of ribbels) kunnen vervelende frequenties en slingereffecten opleveren.

De hoogte van het zwaartepunt van een fiets heeft invloed op onze stuurcorrecties. Hoe hoger, hoe meer tijd we hebben om te corrigeren. Zolang we rechtuit rijden is een laag zwaartepunt stabieler. Dit voordeel verdwijnt, als we snel moeten reageren om putjes of stenen te vermijden. De gewichtsverdeling (plaats en hoogte van het zwaartepunt) is belangrijk; bij veel gewicht op het voorwiel, zal de fiets sneller reageren op verdraaiing van het stuur. De wielbasis heeft ook grote invloed op de besturing van de fiets. Lange fietsen, als tandems, zijn veel stabieler dan hun eenpersoons collega met dezelfde geometrie. Ze hebben uiteraard wel meer wegdek nodig om te manoeuvreren. Vouwfietsen en korte wielbasis ligfietsen en zijn berucht zenuwachtig, maar extreem wendbaar. Er zijn ligfietsen waarbij de rijder een cirkel kan draaien met een hand aan de grond. Op een omafiets rust nagenoeg alle gewicht op het achterwiel; er hier sprake van "understeer": de stuuruitslag is relatief groot voor de bocht wordt ingezet. Als je op kampeervakantie alle spullen op de achterdrager vervoert, krijg je hetzelfde effect. Ga je dan even naar de bakker, als je de tent hebt opgezet, moet je weer wennen aan het directe sturen van de fiets. Ook als je als een ligstuur monteert, komt er meer gewicht op het voorwiel en de fiets neigt naar "oversteer". Bij een kleine stuuruitslag ga je al de bocht in.

Alles wat meedraait met het stuur noemen we het voorframe. Het is fijn als het zwaartepunt van het voorframe zo dicht mogelijk bij de draaias van het balhoofd ligt. Kinderzitjes en bagagedragers bevestigd aan het voorframe, zijn lastig. Er zijn diverse krachten die op het voorframe van de fiets werken. De allerbelangrijkste is het stuurkoppel, de kracht die de rijder uitoefent op het stuur. De bewegingsenergie, het gyroscoopeffect in ons voorwiel, zorgt voor extra stabiliteit. Dit is de bekende truc van het moeizaam verdraaien van een roterend wiel in je handen; deze kracht is klein t.o.v. stuurkoppel, maar neemt toe met de omtreksnelheid en de massa van het wiel. Een andere stabilisator is de geometrische kracht, die door de naloop bewerkstelligd wordt. Deze neemt toe naarmate de effectieve naloop M (mechanical trail) uit FIG.1 groter wordt. Deze drie krachten werken samen om de fiets rechtdoor te laten lopen. Er werken nog meer krachten op het voorframe, zoals de wrijving van de banden en aerodynamische krachten (zeker bij een dicht voorwiel). Ook de stootkrachten van hobbels en kuilen in het wegdek, komen via het voorframe tot ons.

Bij experimenten heeft men met behulp van een tegen roterend vliegwiel, de gyroscoopkracht geëlimineerd. De fiets wordt dan wel minder stabiel (bijna niet met losse handen te rijden), maar blijft bestuurbaar. De meeste fietsontwerpen zijn zelf corrigerend; de fiets zal na het nemen van een hobbeltje weer rechtuit willen. Bij een, door de geometrie bepaalde, verdraaiing van het stuur, zal de fiets een ingezette bocht gaan volgen. Een criteriumracer moet heel snel van richting kunnen veranderen; de bouwer kiest dan voor weinig stabiliteit.

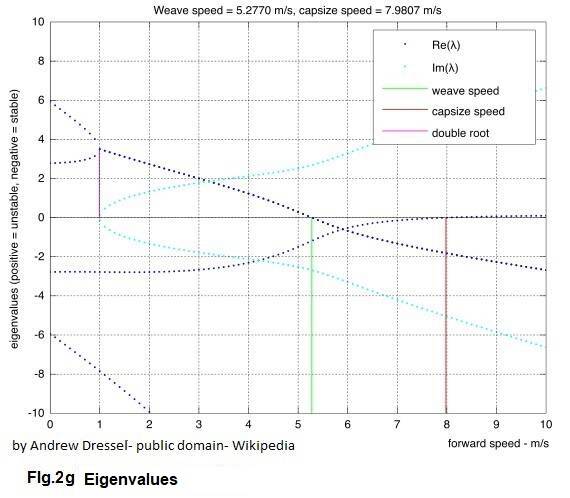

Voor elk frame geldt dus, dat de fiets pas stabiel rijdt vanaf een bepaalde snelheid; dit stabiele gebied kent ook een bovengrens (zie FIG.2g). Als de snelheid van een rijderloze fiets te laag wordt, zal de fiets gaan slingeren en omvallen; bij snelheden boven het stabiele gebied zal de rijderloze fiets in een trage bocht naar links of rechts omvallen (kapseizen). Om stabiel te zijn, moeten de eigenwaarden negatief zijn (de blauwe puntjes-lijnen, grafiek 2g); bij lage snelheid (slingering) zijn de eigenwaarden negatief vanaf 5,3 m/s; vanaf deze snelheid is de fiets stabiel tot de kapseis snelheid bereikt wordt bij 8,0 m/s.

Bill Patterson heeft veel werk gemaakt van het zoeken naar een formule, om voor zeer diverse fietsen een goede geometrie te kiezen. De kern van zijn betoog is dat de fiets bij lage snelheid, uit zichzelf een bocht wil gaan maken (positieve veerkracht) en zich bij hogere snelheid tegen verdraaien van het stuur verzet (negatieve veerkracht). Hij heeft in zijn artikelen uitgebreid beschreven, hoe de metingen van de belangrijke gegevens plaats moeten vinden. De formule is tegenwoordig ook via internet in te vullen.

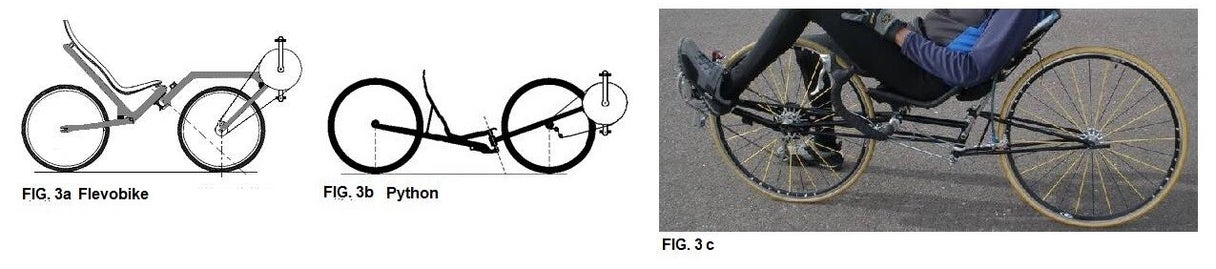

Sommige ligfietsen wijken in geometrie sterk af. De Flevobike heeft een grote naloop en wordt meer vanuit de heupen bestuurd. Dat vergt gewenning en is op de driewielige versie wat makkelijker te leren De Python heeft zelfs een voorloop en de enige stabiliserende factor is nu het optillen van het frame tijdens verdraaiing van het stuur. Achterwiel bestuurde tweewielers zijn zeer schichtig. Die van Dennis Renner, FIG.3c heeft een beperkte draaiing door wringing van het zitje en schijnt voldoende stabiel te zijn.

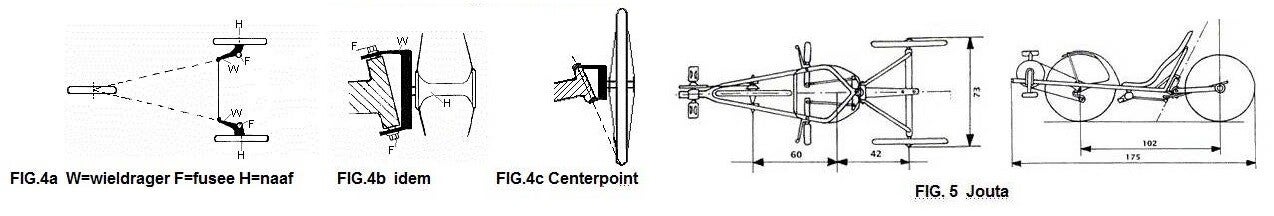

Driewielers met twee sturende voorwielen hebben een met de auto vergelijkbare stuurproblematiek. Wanneer we met zo’n driewieler een bocht maken, zal het wiel aan de binnenkant een kleinere draaicirkel moeten beschrijven dan het buitenste wiel. Beide wielen zijn d.m.v. het stuurstangstelsel met elkaar verbonden. De vorm van het trapezium wordt bepaald door de afstand naar ‘t midden van de achteras: het Ackermanprincipe (FIG.4a). In de besturing kunnen energieverliezen ontstaan door slecht sporen (niet evenwijdig lopen van de wielen). Als de wielen naar binnen wijzen is er “toespoor”; “uitspoor” is het naar buiten wijzen van de wielen, dit leidt tot instabiel gedrag en moet vermeden worden! Beide leveren extra wrijving en slijtage van de banden

Als de hoek tussen voorwiel en wegdek zo gekozen is, dat de hartlijn door de fusee het wegdek snijdt op het vlak door het wiel, heet dat centerpointbesturing (zie FIG.4c) snijdt de hartlijn door de fusees het wegdek door het vlak van het wiel. Gewoonlijk wordt dit toe gepast bij 3 of 4 wielers, maar soms ook op moderne tweewielers. De fusee zit dan meestal midden in het wiel. Het wiel heeft dan de vorm van een pannendeksel. Zeker als je een enkel sturend voorwiel met fusee neemt, moet je voor centerpointbesturing kiezen. Bij constructie volgens FIG.4c mag je geen bredere of smallere banden monteren en je kunt geen vering inbouwen, want dan spoort de fiets niet meer. We zien dit terugkomen bij Dasher. Het draaipunt van de wielen wordt gevormd door de fusees F (zie FIG.4b). Deze dienen schuin naar binnen (5-10°) en naar achter te hellen. Een nadeel van centerpointbesturing is, dat speling in het stuurstang-stelsel of de fuseepen zeer snel tot een z.g.n. shimmy leidt! Dit is een trilling om de lengteas van het voertuig. Bij twee sturende voorwielen kiest men daarom een wat steilere hoek (ook wel K.P.I. genoemd); het snijpunt met het wegdek valt nu tussen de wielen. De afstand tussen snijpunt en wielvlak noemt men de schuurstraal. Beide waardes zijn bepalend voor 't stuurgedrag van de driewieler, met name voor stabiliteit en het zelfcorrigerend effect bij het uitkomen van de bocht. Een grotere schuurstraal levert een sterker zelfcorrigerend gedrag op. Maar de besturing wordt zwaarder en het kost energie. Dit komt door extra wrijving (en daarmee extra slijtage van de banden). Centerpointbesturing wordt vaak gebruikt voor Human Powered Vehicles, maar met name om de stabiliteit op topsnelheid te verbeteren, wordt soms gekozen voor bewuste afwijkingen van het Ackerman-principe en/ of een licht toespoor.

.

In FIG.5 zien we een driewieler met achterwiel besturing uit 1985 van de Nederlandse fabrikant Jouta. Het weggedrag van deze driewieler, met een z.g.n. “kantel-knik” besturing, is niet zelfstabiliserend. Bij voorwielbesturing zal het voertuig na het uitkomen van de bocht uit zichzelf weer rechtdoor willen gaan, zoals een auto; bij dit fietsje moet je blijven sturen. Het voorste deel van de fiets gaat hellen in de bocht; net als een tweewieler. Alleen wordt die hellingshoek niet bepaald door de snelheid, maar door de balhoofdhoek van de achterkant. Er ontstaat een compromis: bij te langzaam nemen van de bocht wil de rijder naar binnen vallen. Bij het te snel nemen van de bocht wil de rijder naar buiten. De constructie is eenvoudig en door het lage zwaartepunt is de wegligging redelijk stabiel. De wielen van een driewieler ondervinden zijwaartse krachten in bochten; kies dus voor dikkere spaken en/ of kleinere wielen. Houd er rekening mee, dat de remmen op de parallelle wielen met dezelfde kracht aangrijpen: anders wil hij de bocht om! Ook de keuze voor een enkel sturend achterwiel is mogelijk, o.a. te vinden bij de Amerikaanse Sidewinder. Bij hogere snelheden ( > 40 km/u) zijn deze driewielers niet echt stabiel; een stuurdemper helpt om shimmy's te voorkomen.

Er zijn door diepgravend rekenwerk nieuwe inzichten ontstaan over fietsstabiliteit. De combinatie van mensen van Nederlandse TU's (Schwab, Kooiman, Meijaard) en Cornell University (Ruina, Papadopoulos, Hand) heeft veel vruchten afgeworpen. Op basis van theoretische berekeningen, heeft men een tweewielertje gebouwd met een kleine voorloop, terwijl de gyroscoopkrachten van de wieltjes door tegenrotatie worden opgeheven. Traditioneel denkend, zou een dergelijke combinatie nooit een zelfstabiliserend fietsje kunnen opleveren; toch is het fietsje stabiel, wat de juistheid van het theoretisch model aantoont. Dit fietsje is nog geen nieuw frameontwerp, maar slechts een veredeld rijderloos stepje met rolschaatswieltjes. We zijn benieuwd of er ook echte fietsen op basis van dit rekenmodel gemaakt kunnen worden.

TEN SLOTTE: LEESVOER EN DOWNLOADS VIA HET WWW:

Een rekenprogramma naar aanleiding van de artikelen van Bill Patterson vindt u op: http://www.wisil.recumbents.com/wisil/trail.asp

Sheldon Brown via de pagina's van Jobst Brandt: http://www.sheldonbrown.com/brandt/gyro.html Er staat ook nog een artikel over shimmy's.

T.Foale: www.tonyfoale.com/Articles/index.htm o.a.: Basic principles of Balancing en Experiments with steering geometrie (engels-MBOniveau)

De Flevobike fanclub en achterwielbesturing van 2 en 3-wielers van Erik Wannee http://wannee.nl/hpv/abt/index.htm

Een redelijke beschrijving in het Engels: https://www.cyclingabout.com/understanding-bicycle-frame-geometry/

Boeken: Bicycling Science - D.G. Wilson ( with contributions of J.Papadopoulos ) third edition 2004 ISBN: 0-262-73154-1

Motorcycle Handling and Chassis Design: The Art and Science - T. Foale second edition 2006 ISBN: 8493328634

Er is een nieuwe kijk op fietsbesturing met veel inbreng van TU-Delft, in combinatie met Cornell University, maar dit is voor liefhebbers met een wiskundeknobbel, zie: http://www.bicycle.tudelft.nl/ en http://ruina.tam.cornell.edu/research/topics/bicycle_mechanics/stablebicycle/index.htm

A simpler story: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9cNmUNHSBac

Hier vind je de ontwikkeling van de theorie: J. Meijaard, J. Papadopoulos, A. Ruina, A. Schwab: Historical Review of Thoughts on Bicycle Selfstability

Daarnaast staat er ook een duidelijk uitgewerkt onderzoek met de pakkende titel: 1201959SOMtext.pdf

J.D.G. Kooijman: Experimental Validation of a Model for the Motion of an Uncontrolled Bicycle (T.U.niveau)

Jaap Meijaard c.s.: Linearized dynamics equations for the balance of a bicycle: a benchmark and review (T.U.niveau)

Een robot: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mT3vfSQePcs

Ook leuk, Human Power USA: http://www.hupi.org/HPeJ/